DUET - Poet & Photographer

Media reviews and articles

DUET - Poet & Photographer (Book Reviews)

Poetry by Elizabeth Burk (Breaux Bridge, Louisiana and New York)Photography by Leo Touchet (Breaux Bridge, Louisiana)

Photo Circle Press, 2018. Pp. 51. $17.50. Paperback

Louisiana Literature – Volume 222

by John ZhengDuet: Poet & Photographer is a conversation of poems and photographs by Elizabeth Burk and Leo Touchet. Burk is a psychologist who has published two fine poetry chapbooks, Learning to Love Louisiana and Louisiana Purchase; Touchet is a self-taught photographer who has published photographs in Life, Time, Fortune, The New York Times, The Washington Post, Oxford American and books of photography including Rejoice When You Die: The New Orleans jazz Funerals. The collaboration of this creative couple resulted in a fascinating book of 23 stunning black and white photographs accompanied by 23 exceptional ekphrastic poems. In her preface, Burk says that this book "represents, for us, art in conversation-we are not only collaborators in life and marriage, we are also now collaborators in co-creating an art form." These photographs and poems, says Touchet in his preface, "have equal value."

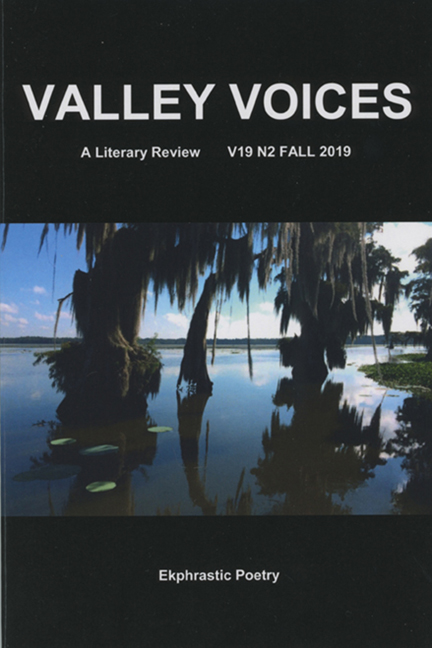

As a visual person, Touchet believes that a photograph is worth a thousand words. "Cypress Trees in Lake," taken at Atchafalaya Basin Swamp in Louisiana, is like an animated image that requires the viewer to take time to consider the ingredients of its composition. Here the empty space fills the center and the two cypress trees are positioned on either side to create a perfect duet or balance through the touching of their limbs hung with Spanish moss. The third tree, a smaller one or simply a trunk, does not look like an unwanted intrusion but like an inseparable connection between the two trees. The trees' reflections in the water function as necessary foreground to enhance the composition while the horizontal line of the lakeshore functions as uncluttered background. Because the darker image of the trees is set against the gray lake and sky, the scene catches a surreal moment of the natural world and thus reinforces an eerie atmosphere.

While Toucher's photograph presents his interpretation of a scene in nature through his powerful grasp of tonal range, Burk's "Hush over Atchafalaya," which goes with the photograph, enlivens the photograph with vivid images of wildlife. She becomes a nature watcher and tells about a southern world shared by both human beings and wildlife:

Beyond the ragged camp

a sagging wooden plank stretches back

into the swamp. It is barely dusk, heat melts from

the day, the moisture clings. A weathered outboard

motor murmurs its way through the murky waters

of the bayou. A white heron on the shore watches,

still as dawn; dragonflies hover above. Two baby beavers

peer from their hiding place inside a hollow log.

Around a bend, the river widens,

massive trees trunks rise from the water, ancient limbs

hang heavy with moss. Alligators glide by, grinning

jaws skim the water's surface, their scaly bodies submerged.

Silvery cypress stumps poke through stagnant waters

like fixed bayonets, ghosts of a forgotten war.

In the river's reflections, a hidden universe beckons

as the boat slips through the channel leaving no trace.

However, it is interesting to note that Burk's "Hush over Atchafalaya" is not exactly an ekphrastic poem on Toucher's "Cypress Trees in Lake." Burk often shares with her husband poems she-has written. When reading "Hush over Atchafalaya," Touchet responds, "I have just the photograph to go with that poem." It is a good match. In Burk's words, it is "ekphrasis in reverse." This poem is a narrative composed of four quatrains. The poet releases her imagination on a swamp tour. If Touchet's photograph depends on the natural imagery chosen by him, Burk's poem relies on the creative working of poetic imagination. In other words, what Touchet sees through his lens and what Burk sees through her mind's eye are not boundaries but jumping stones for their creative and artful expressions respectively, showing their aesthetic experiences gained from their encounter with nature.

"Mesquite Flats Dunes" is another stunning photograph captured through Touchet's keen eye. Taken in Death Valley National Park in 1996, this black and white photograph is erotic and evocative. The high-contrast image enhances the shapes of the windswept sand dunes that arouse an imagination of a feminine body (a bare breast, a buttock or a reclining back represented by the white part of the shapes) and of a low-cut dress, a robe or a cover represented by the black part of the shapes. One characteristic of this visual image is that it possesses a constant flow of consciousness through associative thinking that juxtaposes the image with desire, peace, and action. Viewing it and giving it a moment to imagine is an aesthetic experience to gain an appreciation of art through the working of eye and mind. If it were a color print, it might lose the impressive quality of associative thinking caused by the high contrast of black and white.

Burk's poem, "Desire," interprets Toucher's "Mesquite Flats Dunes" in an imagistic way. It possesses the same quality of tension between the shapes, the colors, the reality and imagination:

with your obsidian grace

bend, blend, dissolve me

into the heat of desire

before the wind scatters our particles

reconfigures us

In the first stanza, the poet visualizes the high contrast of sand dunes as a woman with a moonstone body and a cover of obsidian grace. The use of personification to humanize the sand dunes as a body to be covered with grace progresses smoothly into actions of love in the second stanza-bending, blending and dissolving into the heat of desire. And the third stanza gives an urgency. Time waits for no one, and the moment of nowness must be grasped before the body is scattered into sand particles and reconfigured by wind. "Desire" is a well-imagined ekphrastic poem. On the surface, it offers an interpretation of the photograph with a focus on the personified sand dunes, but behind it is the human desire aroused by nature and by art forms gained from nature. This binding of the external images and the internal desire makes the poem exceptional.

Ekphrasis is not just a poetic description or representation inspired by a piece of visual arts; more importantly but also a continuation through the play of imagination or the interplay of visual art and language art. It is a genre that involves the poet's reflection on a piece of art, rearrangement of images, and recounting of imagination through narration. Touchet captures the moments in time that exert visual effects through his photographs, and Burk grasps a good understanding of ekphrasis through her interpretation and imagination, and their works in Duet should suffice.

LOUISIANA: A DUET OF PHOTOGRAPHS AND POEMS

An article about Ekphrastic Poetry and photos by Leo Touchet and Elizabeth BurkValley Voices - Volume 19 - Fall 2019

by John Zheng

LOUISIANA: A DUET OF PHOTOGRAPHS AND POEMS

Elizabeth Burk is a psychologist who divides her time between a practice and family in New York and a husband and home in southwest Louisiana. Her two earlier poetry collections - Learning to Love Louisiana and Louisiana Purchase (Yellow Flag Press) - describe in part the transition from living in New York to living in the heart of Cajun country, where life revolves around music, dancing, and food. A Pushcart nominee, her poems have appeared or are forthcoming in Atlanta Review, Rattle, Calyx, Southern Poetry Anthology, Spillway, About Place, Nelle, Poetry Quarterly, Passager, Gyroscope, Louisiana Literature, Valley Voices, and various other journals and anthologies. Her latest collection, Duet-Poet & Photographer, is a collaboration with her husband Leo Touchet.

No. 0250 - Iberia Parish, Louisiana 2014

Cypress Tree on Lake Dauterive |

No. 1462 - Vermilion Parish, Louisiana 1990

The Vermilion River South of Abbeville |

Moss droops from hanging branches

like the moss he draped

over my shoulders, leaving

prickly stickers in my shirt -

Cajun fox he called it,

my Louisiana man, wooing me

to the only land he loves.

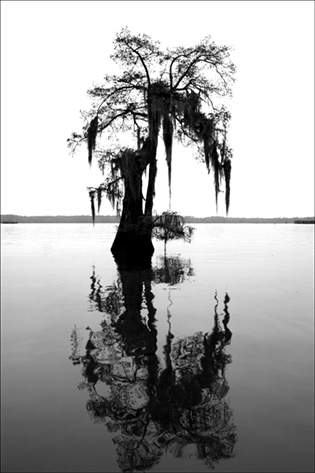

Two Donkeys along Hwy. 82 North of Abbeville

No. 0713 - Vermilion Parish, Louisiana 1987

House and Oak Trees |

No. 1462 - Iberia Parish, Louisiana 1990 Scene along Hwy 82 North of Abbeville |

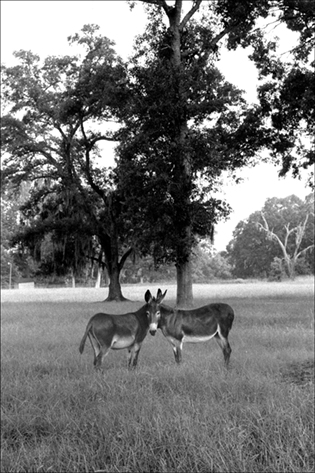

A sugar cane field after harvest

(Photo No. 1108)

no valleys, not even rolling hills,

it has an allure all its own.

this stretched out steamy expanse

of wet grass and moist air from

Opelousas down to Catahoula,

west through the back roads to

Indian Bayou, Mouton Cove, down

to Isle des vaches, Forked Island

These muddy, broken-down, barren

landscapes can tug a person's heart

right out of her body, lift it up

into endless sky where it floats

like clouds over sugar cane

and rice fields, towns no longer there,

disappeared after hurricanes

plowed through. Down here,

you can't live under trees

or by the water, my husband warns,

a perpetual struggle between us

as I long for both.

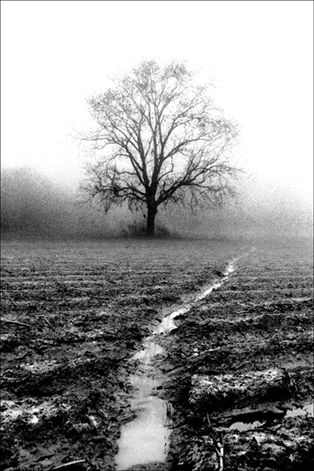

No. 0900 - Vermilion Parish, Louisiana 1990

A barn in a field in the winter |

No. 1127 - Vermilion Parish, Louisiana 1990

A sugar cane field after harvest |

(Photo 0900)

evokes the English countryside

there are no thatched cottages

no smoke puffing from a chimney

or from the bishop's fragrant pipe-

the only pipes here lie in culverts,

draning the waters upon which

all of Louisiana floats, sinking daily

further into the sea

Cypress Tree Stump

(Photo 1841)

momma pirouetting gracefully

in the murky riverbed, baby rising above

perched atop their shoulders

mouth open, howling at the sky.

Cypress Trees

(Photo No. 1966)

pours down all day

a hush as the curtain rises -

we are the trespassers

in this dense hidden drama.

Silence. Do not disturb. You are

but a guest in this untouched world.

No. 1477 - Terrebonne Parish, Louisiana 1987

Scene in the marsh where salt water encroachment killed the cypress trees in what was originally a fresh water swamp |

No. 0717 - Terrebonne Parish, Louisiana 1988

Scene in the marsh where salt water encroachment killed the cypress trees in what was originally a fresh water swamp |

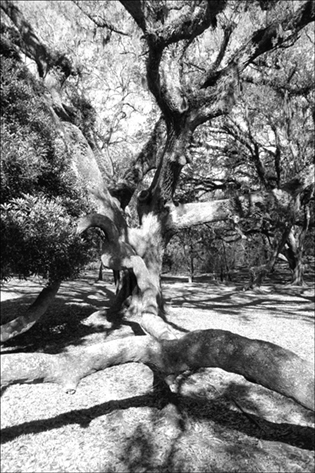

No. 1460 - Avery Island, Louisiana 2014

Live Oak Tree |

No. 1553 - Avery Island, Louisiana 1990

Oak Tree covered in vines |

Moss covered cypress trees

(Photo No. 1114)

The sky blackens, water

pours down all day

our backyard pond fills

to the brim, then overflows,

water rising up through the grasses,

up to the deck of our house.

When I look out the window

it seems as though we're floating

on a houseboat deep into

the Atchafalaya Basin surrounded

by cypress trees. Days later,

standing water's still there -

will it ever drain or is this life

in Louisiana-a perpetual bathtub

in our back yard?

No. 1599 - New Orleans, Louisiana 1990

Couple kissing on Riverwalk |

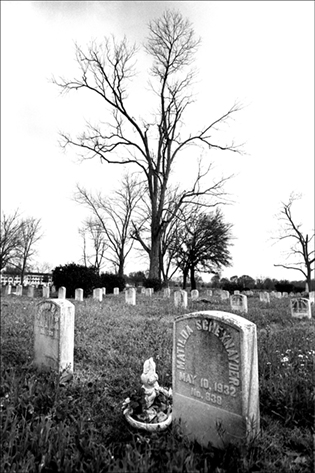

No. 1821 - Carville, Louisiana 1968

Cemetery at Hospital for Leprosy |

Photographing black & white landscapes was something I did everywhere while looking for the perfect composition. I liked to frame the photos in my camera rather than crop them in the darkroom. All of the images here are full-framed photos and not cropped.

The photogaph No. 1821 at the Hospital for Leprosy was done on assignment for Look Magazine. Some of the swamp scenes were taken while working on stories for The New York Times. The remaining photos were shots I grabbed while traveling.

DUET: Interview with Leo Touchet and Elizabeth Burk

An article about Ekphrastic Poetry and photos by Leo Touchet and Elizabeth BurkValley Voices - Volume 19 - Fall 2019

by John Zheng

DUET: AN INTERVIEW WITH

LEO TOUCHET AND ELIZABETH BURK:

Zheng: Can you give our readers a highlight of yourself as a photographer and as a poet?

Leo: In 1958 I enrolled in Architecture School at the University of Southwest Louisiana (now the University of Louisiana Lafayette). There I was introduced to art, composition, form, light and perspective. In my photography, I’ve tried to use all of these elements, particularly composition. On a visit to the Museum of Modern Art (MOMA) in 1965, I was captivated by an exhibit of the photographs of the French photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson. After that, I spent much of my free time studying the works of great photographers such as Henri Cartier-Bresson, Paul Strand, Eugene Smith, Edward Steichen, and Gordon Parks. Six months later, I bought a plane ticket to Vietnam to learn to be a photographer.

Burk: By profession I’m a clinical psychologist, but I was a French lit major in college and I especially liked the early French surrealist poets like Baudelaire, Rimbaud, Breton. About 20 years ago, I began to attend writing workshops and wrote my very first poem—a funny rhyming roast/toast for Leo’s birthday. Eventually I began to write and read poetry more extensively. A patient of mine, a poet, introduced me to Billy Collins and Mary Oliver, opening my eyes to poetry that is accessible and that moved me.

I began exploring poets such as Sharon Olds, Louise Glück, Anne Sexton, Dorianne Laux, and especially narrative poets who incorporated their own life stories into their poetry, as I frequently do, hoping these events and stories will resonate with others. I began to submit my poetry for publication, and eventually three of my poems were accepted for publication by the Louisiana Review—a very validating experience. I continued to submit my poems and acceptances began coming in along with the many rejections we poets all seem to receive on a regular basis. I compiled some of my Louisiana poems into a chapbook which took the form of a themed narrative: meeting Leo, our relationship, my impressions of Louisiana Cajun country. This chapbook, Learning to Love Louisiana, was published in 2013 by Yellow Flag Press. My next collection was called Louisiana Purchase, as we had just bought our first house in Louisiana. I continued to write, publish and began to give readings. Then we embarked on our joint project, Duet: Poet & Photographer which came out last September, and I’m planning to compile several other themed collections for more books. Becoming a "a poet"—has been and still is exciting, stimulating, often frustrating, a calling, a preoccupation, an obsession even, but always an adventure—I’m always excited to see what I’ll write about next.

Zheng: Duet is such an interesting conversation of poems and photographs. How did you two think of starting this ekphratic project?

Touchet: Several years back, I saw and heard Liz reading a poem which was inspired by a painting at a reading in Lake Charles, Louisiana. It was the first time I had ever heard of this type of poetry. The term ekphrasis sounded more like some strange tropical disease rather than literature. I was impressed with how the poets were able to write poems inspired by other visual art forms. The poets read poems which were inspired by paintings, and paintings were shown which were inspired by poems. Later, Liz conceived the idea of having six poets write poems inspired by photographs from my exhibit, People among Us, at the Acadiana Center for the Arts in Lafayette, Louisiana. Each poet selected two photographs from my exhibit and wrote poems inspired by the photographs. The event, Image to Word, was a poetry reading which took place in the exhibit gallery. This event sparked the idea to do a book together. Collaborating with a poet on a book was something entirely new to me. After that, we began talking about the process which evolved into the book.

Burk: Several years ago I took part in a project called Writing on the Walls, sponsored by the Hudson Valley Museum of Contemporary Arts in Peekskill, NY. Two of my poems were accepted and hung on the walls besides my chosen works of art, and a reading took place a few months later. This was my introduction to "ekphrasis." I later participated in an ekphrastic reading in Lake Charles, Louisiana, where Leo saw me read for the first time. He was intrigued by the poets’ ability to translate visual images into words, and suggested I look through his photographs. These two events later inspired me to put together a poetry event "Image to Word," which was based on the photographs from Leo’s exhibit "People Among Us" at the Acadian Center for the Arts in Lafayette, Louisiana. Leo had always encouraged me to use his photographs as inspiration for poems—especially his dune photos—but I was initially intimidated by the idea of writing from abstract images. Over the years, I’ve become more secure and fluent in my writing, better at allowing a photograph and works of art act as a trigger for a poem, at letting my imagination take me wherever it wants to go. So putting a book together—poems and photographs— seemed a natural next step.

Zheng: Do you have anything to share with readers about the process of selecting photographs or writing ekphrastic poetry?

Touchet: Liz had access to my files and began writing with certain photos in mind. She then showed me the poems and photo selections she had made. In some cases, I felt I had other photos which fit better with the poems. In some cases, she accepted or rejected my choices. I felt her poems were more important to the project and some of the photos selected were not my choices. They were not what I considered to be my best photography. We also had a difference of opinions as to how to sequence the photographs and poems. In the end, we submitted two versions of the sequencing of the book to the editor. He selected Liz’s version.

Burk: My first inclination when writing is as a story teller—I like to make up stories and to tell somewhat amended versions of my own life stories. So I tend to look for photographs with people, or even landscapes, which will inspire some kind of narrative. I let my unconscious do the associative work. I look at the photograph, jot down some thoughts, associations, leave it, come back to it, and try to stay open to whatever comes to mind. Ekphrastic writing is especially intriguing as the work of art acts simultaneously as a mirror of the inner self and as a reflection of what the poet sees. Usually I try to avoid a description of the photograph itself, including only enough details to make the poem coherent. Oftentimes, I see something that others do not see. For example, in one of the flower photographs I saw a priest at the altar, triggering memories of my first time in a catholic church as a child. In regards to selecting photographs for Duet, several times Leo felt that there was a possibly better quality photograph for a particular poem than the photograph I had initially selected. Usually I agreed without quarrel, but sometimes I disagreed and we ended up com- promising on a third photograph. But for the most part I deferred to him on the photograph choices, as I respected his desire to present his own work in the best possible light.

Zheng: Liz, what struck you particularly when you saw Leo’s photograph of Mesquite Flats Dunes on page 38 of Duet?

Burk: I immediately saw abstract forms in a composition that was extremely compelling to me—two bodies blending, flowing together, superimposed upon one another, graceful, sensual, erotic. I found myself mesmerized by the shapes of these bodies intertwined. These abstract photographs in particular are like Rorschachs, the famous Inkblots we psychologists use to get at someone’s inner world. The viewer (or writer) projects whatever comes from their own psyche onto the image. That’s what makes ekphrastic poetry so exciting, such an adventure, to see what the image evokes from the writer’s own experiences, memories, dreams, associations.

Zheng: By the way, Leo’s photograph challenges visual thinking. Can you share your experience of writing "Desire" that corresponds to Leo’s photograph? Our readers would be interested in your writing process.

Cover my moonstone bodywith your obsidian grace

bend, blend, dissolve me

into the heat of desire

before the wind scatters our particles

reconfigures us

Burk: This photograph was less challenging than some others in that I immediately envisioned two bodies—one white, one black, lying together—very sensual, graceful, with a lucidity and beauty in the forms. There’s also a complex interplay of shadows and light and this combination conveyed to me a serenity, a spiritual quality as well. I wanted the poem to convey, to mirror the sensuality and eroticism I saw, but to be spare, lean, with only a few lines to let the photograph really speak for itself. I also wanted to address what I saw as an image of a black body merged with a white body, which for some represents a controversial, complex issue. I tried to do this indirectly with my last two lines—although those lines can be interpreted in any number of ways.

Zheng: Leo, your photographs of sand dunes produce a striking visual effect through the contrast of black and white and shapes. The one Liz wrote "Desire" about seems to show especially an abstract impressionism. Can you talk about shooting photographs of sand dunes with abstract images?

Touchet: Earlier in my career, I was impressed with the abstract photographs of Aaron Siskind. I met him and had a long discussion regarding his migration to abstract photography. I didn’t understand much at the time. My first experiences with abstract art was in a design class in college. Almost forty years later, the dunes photos became my first photos moving toward abstract images.

Zheng: The composition of the beautiful shapes of your dune photographs depends on the time of day and effects of light and shadow. What would be the best time to shoot shadows of the dunes?

Touchet: I was only able to photograph during the first half hour and the last half hour of the day. Once the sun moved up into the sky, the shadows began to disappear. Some of the dunes were miles away from any road. In those cases, I packed a tent into the dunes in the afternoon to photograph at sunset and again then next morning at daybreak.

Zheng: Some of your dune photographs show the power of visual association that helps a viewer to see the natural beauty of female body. How did you catch those images of abstract beauty from dunes?

Touchet: Probably by instinct. While photographing, I concentrated more on the composition of the photos. With the short time available to photograph, I had to move quickly from one photo to another and didn’t have much time to think of any abstract associations.

Zheng: Another photograph that strikes me with contrast of black and white and gray is the "Man Reading Book on Sidewalk." Liz, how did you imagine writing about it? Did you exchange ideas with Leo about the photograph in order to get a feel for it?

Burk: I asked Leo which is his favorite photograph, and he replied it was "Man Reading Book on Sidewalk" in Catalonia. I was intrigued primarily by the old man sitting outside in shadows reading something, I couldn’t tell what. My associations to it, especially with it being in Catalonia, a hotbed of political unrest, were of my father, who was a voracious reader of history, and very interested in politics. The photograph enabled me to tell a story involving my father and growing up in the umbrella of his political leanings. And my own political leanings crept into the poem as well. When I asked Leo why it’s his favorite photograph, I expected a story about the old man—perhaps he was reminded of his own father or grandfather. His answer astonished me: "Because this photograph has black, white and every shade of gray." It was something I never would even have con- sidered, much less noticed. That’s the difference between an image person and a word person! But that conversation had an effect on my poem—I looked at the photograph in a new way and it inspired a re-write of the last two stanzas where I incorporate the idea of "black, white and gray" and I believe it’s a better poem for that enlightening conversation. And with that in mind, I can say our process was truly interactive.

Zheng: Leo, as a photojournalist who has traveled to over fifty countries, what was your most adventurous experience?

Touchet: Almost every assignment presented an adventurous experience, with some being exciting and some being dangerous. Anytime someone goes out into the world to a location or culture he is not familiar with, I would classify that as an adventurous experience.

Zheng: Liz, as a poet, what have you learned from living in Louisiana? And how did you describe about it in your poetry?

Burk: My first two chapbooks, Learning to Love Louisiana and Louisiana Purchase, were based on my experiences in Louisiana. Coming from New York City and its mountainous tree-filled suburbs, I was struck by the flat-filled, wide open landscapes—the miles and miles of sugar cane and rice fields. A visit into the Atchafalaya Basin introduced me to the mysterious, magical life of the swamp with the weepy trees, reaching out over sultry swamps, and the limbs of ancient trees reflected back in the murky waters. All these words are pulled from various poems I’ve written describing my impressions of the Louisiana swamps, and the landscape. And I was experiencing it all with a native from Louisiana, who knew the land well. It was exciting and romantic. On our first trip, he pulled some silver moss from a tree and wrapped it around my shoulders, called it "Cajun fox" and I describe this experience in one of my poems. I saw the marshes, the white clouds for mountains, the roseate spoonbills, the live oaks, the sleepy towns that all looked shut down even in daytime. These visual experiences, their impact on me and how I’ve opened my heart to the wide open spaces of the prairie have been incorporated into many of my poems.

I’ve also met incredible people down here, bright, talented, artistic people and I’ve incorporated many of them into my poems as well. There’s such a wealth of creativity in southwest Louisiana—musicians, dancers, playwrights, poets, visual artists, and all kinds of crafts. The place itself inspires creativity—I’ve taken up the harmonica and playing the triangle so I can participate in jam sessions. We’re also surrounded by the Cajun culture: spicy food, the French language and influence, Cajun/zydeco mu- sic, dancing, the continual rounds of jams, bands, pot luck parties—all grist for the poetic mill.

The Cajun people are continually intriguing to me—insular, rough on the outside, warm on the inside, a people who for many years were ostracized by the mainstream culture and therefore learned to survive on their own—it’s a very self reliant culture. In New York we tend to be a little snobby about the south and southerners, so my northern friends often ask me what I do in Louisiana without New York’s cultural events. And my answer is: "There’s so much to do down there that I come back to New York to rest." We live in the country now, near the town of Breaux Bridge in the heart of the Cajun area, where people from everywhere come to experience and participate in the music and dance activities. We have a pond in our back yard with all kinds of wildlife, so I’ve become more attuned to nature. Sitting on our deck with my husband watching a turtle slowly climb up the wooden ramp of a turtle trap was as captivating for me as watching a Broadway play—so I wrote a poem about it. I’ve opened my heart and mind to new ways of experiencing and writing about a culture and landscape very different from my own and it’s both challenged me and changed me in ways I try to capture in my writing.

Zheng: Leo, what’s your current photographic project?

Touchet: For the past few years, I’ve been busy cataloging my photos. All of my past street photography was done with Leica rangefinder cameras, but it’s now too costly to continue photographing with film. I could not afford the new Leica digital rangefinder cameras to do the street photography. I purchased a Fujifilm rangefinder digital camera which I’m slowly learning to use.

Digital SLR cameras are too slow to do street photography. This is mainly due to the time the auto-focus takes to set the shot. Once you see the image in your mind, it is too late to photograph it. Street photography required that one anticipate a photographic opportunity about to happen. With the rangefinder cameras, I could photograph with both eyes open - the right eye on the viewfinder, the left on the scene.

As digital photography has progressed, I find that I no longer have the curiosity or urge to photograph as I did earlier, but I do miss the excitement of doing street photography.

Zheng: Liz, are you still writing ekphrastic poetry or working with Leo on an ekphrastic project?

Burk: I often write ekphrastic poetry as paintings and photographs are frequently used as prompts in my workshops. And it’s always interesting to see what other writing emerges from the group of writers, with an object of art as an associative trigger. I find ekphrasis a fertile ground for inspiration. Leo and I are not currently working on an ekphrastic project together, but I wouldn’t be surprised if we start one again in the not too distant future.